Ideathek

ƒ01

︎

MA-Thesis

, UdK Berlin

︎SoSe 2021

0 Preface

Complexity has become a key concept in the sciences. It contradicts the linear and schematic way of approaching the world around us through static and universal knowledge, but rather promotes the fluid and networked entanglement of phenomena. The approach of complexity is based on the insight that each analyzed situation is multidimensionally and transdisciplinarily informed by a multitude of agencies, contradicting the one-dimensionality of conventional knowledge conceptions. But to remain in a position to understand and actively shape our more and more complex realities, spaces are required that can equally (re)produce these convoluted relations. The way how we deal with knowledge today, our educational and learning spaces but also our working environments in general, dramatically lack these qualities. Also, because they insufficiently incorporate the tools we have at our disposal, namely our contemporary digital technologies, which are the instruments that opened the door for us to detect and analyze complexity on a broad scale in the first place. To think complexly means to think with the help of technology, or put differently: technologically mediated. My project is the attempt to therefore actualize one of our most central spaces of knowledge-interaction: a library. How can we as designers and architects create shared spaces that enable complex modes of knowledge retrieval, exchange, or generation and that frame collaborative cross-border work settings?

When I started my master’s studies at the University of the Arts Berlin in fall 2018, I got into a project group that intended to research possible synergies of digital technologies implemented in spaces of education and learning. Of course, we were aware that this task could hardly be answered by us architects alone, and so we initiated an open format of events and seminars for interdisciplinary encounter and the exchange of knowledge within UdK (Digital Salon). Out of this discourse the question arose how architecture can contribute to more complex modes of learning and working together. In the early stages of the project, I purposely let my attention and interest wander and dug into different fields of research that seemed related. This “undisciplined” way of connecting contents was the basis for the development of the transdisciplinary approach outlined in the following thesis. Correspondingly, in the project different textual lines from different disciplines (inter alia: architecture, philosophy, cultural studies, computer science) converge to form this heterogeneously informed argument. However, the project is neither a conventional architectural project nor a scientific paper. I like to see it as an “architectural essay” that blends conventional forms of presentation into a web-optimized experience.

Contents

1 Research: A media revolution

1.1 Tree-knowledge

1.2 Thinking paper-based

1.3 Hyperlinked reality

2 Interface: computing complexity

2.1 A hybrid data pool

2.2 Networking knowledge

2.3 Mock-up

2.4 Curriculum

3 Architecture: A platform for knowledge

3.1 Virtual and real-world platforms

3.2 Architectural interventions

3.3 Learning-clusters

3.4 Augmentation through apps

4 Conclusion

1 Research: A media revolution

1.1 Tree-knowledge

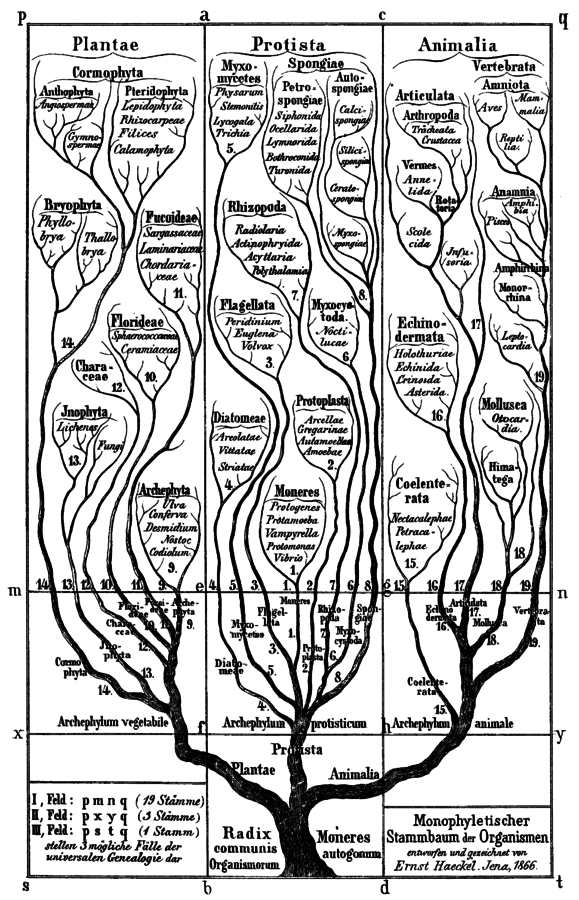

In the aftermath of the enlightenment the emerging sciences were based on a particular form of thought – a conceptual figure for the fundamental organization of the world that can be summed up with the visual metaphor of the "tree". Central in this conception is the hierarchical structuring of knowledge. Thereby a small number of statements defines and controls vast quantities of statements on all subjacent levels – from highly abstract at the bottom, to very concrete pieces of knowledge at the top. This modern knowledge organization seems to be intuitive – even obvious. But this way of making sense of the world is a constructed one. It doesn’t represent a seemingly natural order but rather enforced a very much human made logos on natural phenomena. It’s needless to say that this epistemological regime was and is highly productive, but there was a price to be paid for this hierarchical order.

The genealogical organization only allows linear, one-dimensional relations and thus introduced a binary mode of classifying knowledge separating all entities of the modern knowledge system into fragmented, specialized branches. Therefore, every entity had a fixed position within the overall structure of the tree, its branches, and their inner ramifications/differentiation. In this logic horizontal or cross connections weren't possible. And out of this urge to keep things (literally) in line and therefore manageable, disparate silos of thought and practice (hence knowledge) emerged that then defined the disciplinary landscape of modern sciences.

Another, even more important implication for our case is that with this hierarchical mode of organization the contents of knowledge consequently had to be reduced when referred to on their way down. Since superordinate points received many streams of information coming from above but could only pass on one channel further downwards, the contents had to be merged, synthesized and/or subsumed before. In this process a high percentage of what was written on higher levels got inevitably lost resulting in an accumulative reduction: the further down in the tree-diagram, the higher the level of abstraction and the more detail and nuances are filtered out.

This epistemological reductionism resulted in a form of thought that tended to homogenize and abstract. The universal formal structure was always already there, just waiting for the bits of knowledge to be fitted in. But obviously, the world is and always has been more complex than a simple tree diagram could suggest. Then why was it organized in this reductionist manner? There is of course not one single answer to this question. Many influences contributed to the emergence of this in itself highly complex situation. There is the generally hierarchical/monarchical design of most 19th century societies for example which are themselves based on the far-reaching religious belief of a god-created, natural hierarchy. But I want to suggest that there might be another complementary argument that gives attention to the technological circumstances of the time. Namely that the reduction of complexity and differences was partly inevitable because the systemic, technological parameters didn’t allow for any higher extent of information processing and consequently had to result in a systemic reductionism.

1.2 Thinking paper-based

|

The hypothesis is as follows: The formation of the reductionist tree-knowledge can only be understood by considering the specific socio-technological conditions of the 19th century – a period in which the tree-knowledge got widely distributed in academic spheres and beyond. It was the material milieu for this particular mode of knowledge organization to emerge. The central technological and cultural artefact that shaped the emergence of those systems was the book. Around it social practices and protocols evolved that formed interdependent assemblages of both, technological and social. As the primary mean for knowledge communication and storage the 19th century academic societies created themselves with all their intricate procedures, rituals, normativities around the technological medium of the book. It limited the memory size of the single data carriers. It defined the speed of “reading” or retrieving the data. Its reproduction was tied to the performance of the industrial letterpress printing. The postal sector [defined] the speed of data transmission. An academic library of the time couldn’t be imagined without any ink on paper. Consequently, librarians had to face the incoming stream of knowledge/books with the tools and the organizational protocols (e.g., the library catalogues) available at hand. All these factors defined the overall capacities and performance of the information-processing system. Humans themselves were only one component in the complex of technological, economic, and political conditions in total. And regarding the relatively limited means the librarians had no other choice than applying the method of reduction to make the sheer infinite amount of knowledge manageable or even navigable in the first place. My suggestion is therefore as follows: Knowledge can’t be understood independently from its material context. For the 19th century the increasing imbalance between the quantities of knowledge and the possibilities to process it led to the emergence of an epistemological structure based on reduction through labelling. The contingent metaphor of the tree was just one possible form of structuring. Taking the historical circumstances into account the tree was just more obvious than others. |