1 Research: A media revolution

1.1 Tree-knowledge

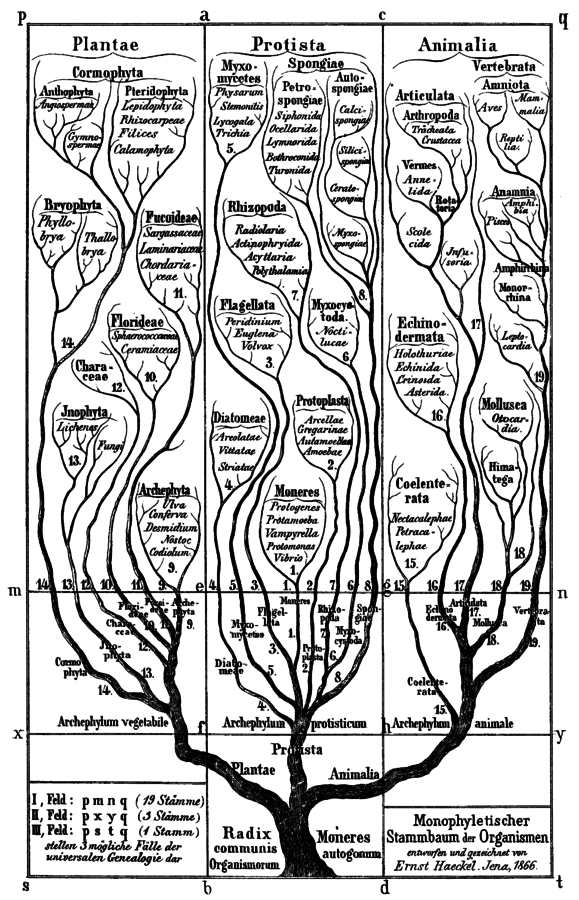

In the aftermath of the enlightenment the emerging sciences were based on a particular form of thought – a conceptual figure for the fundamental organization of the world that can be summed up with the visual metaphor of the "tree". Central in this conception is the hierarchical structuring of knowledge. Thereby a small number of statements defines and controls vast quantities of statements on all subjacent levels – from highly abstract at the bottom, to very concrete pieces of knowledge at the top. This modern knowledge organization seems to be intuitive – even obvious. But this way of making sense of the world is a constructed one. It doesn’t represent a seemingly natural order but rather enforced a very much human made logos on natural phenomena. It’s needless to say that this epistemological regime was and is highly productive, but there was a price to be paid for this hierarchical order.

The genealogical organization only allows linear, one-dimensional relations and thus introduced a binary mode of classifying knowledge separating all entities of the modern knowledge system into fragmented, specialized branches. Therefore, every entity had a fixed position within the overall structure of the tree, its branches, and their inner ramifications/differentiation. In this logic horizontal or cross connections weren't possible. And out of this urge to keep things (literally) in line and therefore manageable, disparate silos of thought and practice (hence knowledge) emerged that then defined the disciplinary landscape of modern sciences.

Another, even more important implication for our case is that with this hierarchical mode of organization the contents of knowledge consequently had to be reduced when referred to on their way down. Since superordinate points received many streams of information coming from above but could only pass on one channel further downwards, the contents had to be merged, synthesized and/or subsumed before. In this process a high percentage of what was written on higher levels got inevitably lost resulting in an accumulative reduction: the further down in the tree-diagram, the higher the level of abstraction and the more detail and nuances are filtered out.

This epistemological reductionism resulted in a form of thought that tended to homogenize and abstract. The universal formal structure was always already there, just waiting for the bits of knowledge to be fitted in. But obviously, the world is and always has been more complex than a simple tree diagram could suggest. Then why was it organized in this reductionist manner? There is of course not one single answer to this question. Many influences contributed to the emergence of this in itself highly complex situation. There is the generally hierarchical/monarchical design of most 19th century societies for example which are themselves based on the far-reaching religious belief of a god-created, natural hierarchy. But I want to suggest that there might be another complementary argument that gives attention to the technological circumstances of the time. Namely that the reduction of complexity and differences was partly inevitable because the systemic, technological parameters didn’t allow for any higher extent of information processing and consequently had to result in a systemic reductionism.